SINGAPORE - Singapore’s ambitions to weave more nature into the city could come at a cost for certain species of birds, which are more prone to crashing into buildings near forested areas, a new study has found.

Led by Singaporean bird scientist David Tan, the study identified six areas linked to future developments – including Tengah and Springleaf – where birds could face increased risk of flying into buildings.

Certain species of resident birds, like green pigeons and emerald doves, often move between forest patches in their search for food, and could face an increased risk of flying into buildings that are located near the forest edge, the study said.

Migratory species, such as the yellow-rumped flycatcher, also face the risk of crashing into buildings near forests, as they seek out forest patches to forage and rest.

The study comes amid Singapore’s City in Nature push, where the Government aims to bring nature closer to places where people work and live.

“For new developments that incorporate forests into their urban design to be truly environmentally friendly, we need to think about more than just managing interactions between humans and wildlife,” Mr Tan, who is pursuing a doctoral degree in biology at the University of New Mexico, told The Straits Times. “Indirect human-induced fatalities like bird collisions should also be considered.”

The phenomenon of birds crashing into buildings is not unique to Singapore. Every year, billions of birds die after smashing into glass buildings that they cannot see or from exhaustion as a result of getting confused by city lights.

In North America alone, nearly one billion birds are estimated to die from flying into buildings annually, and multiple studies have been done on bird-building collisions in small clusters of buildings there.

Mr Tan’s study, published in the journal Conservation Biology in March, marks one of the first city-scale studies into the problem in Asia.

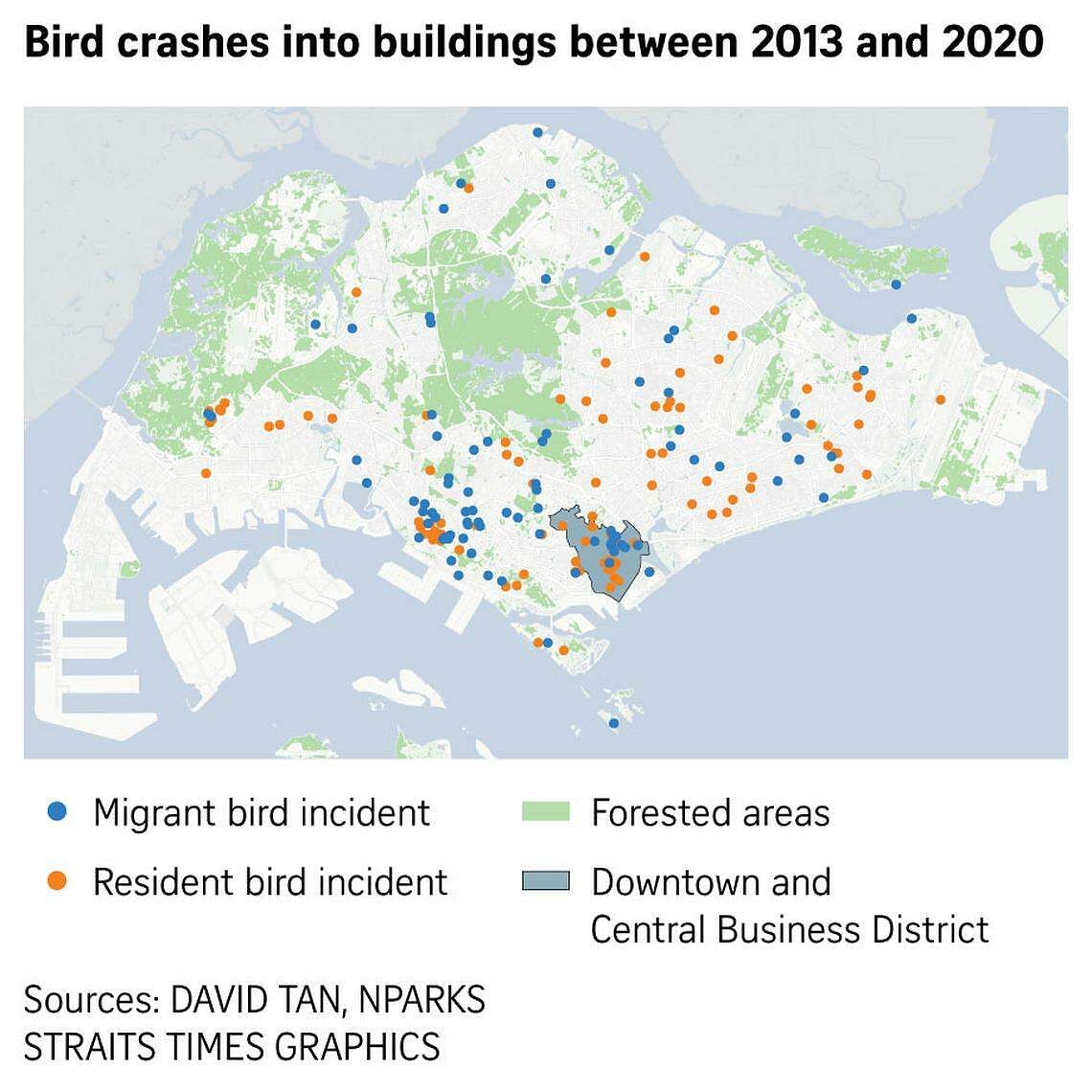

For the study, Mr Tan and his co-authors pored over reports of dead birds submitted between 2013 and 2020 by members of the public on social media or via a hotline manned by researchers from the Avian Evolution Lab at the National University of Singapore. The researchers looked into details such as where the birds were found and the likely cause of injury or death.

A total of 224 birds were determined to have died after crashing into buildings, as they were found at the base of buildings with signs of facial injury or head trauma.

Like crime-scene investigators, the researchers next sought to identify factors that could predict bird-building crashes based on evidence like building and satellite data.

They found that the proximity of forests to buildings was a key driver of these incidents.

Mr Tan said: “Forest proximity is the biggest driver of collisions for both resident and migrant birds because they tend to move between forest patches to forage. So, it is likely that these birds will hit buildings near the forest edge.”

The researchers also identified future collision hot spots from modelling studies based on the Urban Redevelopment Authority’s Master Plan 2019, which shows Singapore’s land use over the next 10 to 15 years.

Other than Tengah and Springleaf, other potential hot spots for bird-building collisions are Clementi and Ulu Pandan, Turf City and Bukit Brown, estates in Punggol End and industrial developments in Pasir Ris.

In particular, new large-scale residential developments were predicted to pose a high collision risk for green pigeons, emerald doves and Ficedula flycatchers as these are near the central, western and southern forest fragments, the study found.

The study did not account for urban development that was not reflected in the 2019 Master Plan, like the proposed development of Paya Lebar Air Base for housing.

The study also highlighted another driver of bird-building collisions: nocturnal blue-light pollution. Blue light has the highest energy in the visible light spectrum. It comes from the sun and artificial sources like white LED lights and smartphones.

In particular, clusters of buildings with high blue-light pollution proved to be treacherous to birds that migrated at night, especially pittas, the researchers found.

This finding was concerning for the researchers, given the dramatic increase in islandwide levels of blue light as LED street lamps have replaced most of the country’s sodium-vapour ones in the name of energy efficiency. However, the researchers pointed out that this discovery could have a silver lining.

Mr Tan said: “Just because blue light is related to building collisions in migrating birds doesn’t mean we should start switching off all our lights at night.

“Instead, we can try to lower the average amount of blue-light pollution, especially during peak migration, by switching our LED street lights to a more orange hue and by shielding our lights to reduce the amount of light pollution directed into the sky.”

In New York, for instance, an illumination commemorating the Sept 11 attacks is switched off intermittently after scientists discovered that nocturnal migrating birds were disoriented by the memorial’s powerful beams.

Bird deaths have consequences for humans too, said Mr Tan. “While birds hitting buildings is obviously not good for birds, from a public health standpoint, we also want to minimise the amount of contact people have with dead wild animals,” he added.

Humans can be infected with bird flu through direct or close contact with infected live or dead birds.

In the light of the paper’s findings, researchers called on urban planners and architects of future and ongoing developments next to and in existing forested areas to pre-emptively make buildings safe for birds.

This will be more cost-effective than retrofitting buildings after bird-building collisions occur, they added.

Dr Karenne Tun, director of the National Parks Board’s National Biodiversity Centre, said the study complements the statutory board’s guidelines, introduced in 2022, for designing bird-safe building interiors and exteriors.

The recommendations, which localise practices from other cities like Chicago and Toronto that minimise such crashes, include making glass less reflective.

This and other suggestions tackle the increased use of glass in modern architecture, which tends to cause birds to crash into buildings as the facades create the illusion of a continuous natural environment.

She said these guidelines can contribute to the Building and Construction Authority’s Green Mark 2021 certification, which aims to encourage the industry to develop green buildings and raise the sustainability standards of Singapore’s built environment.

On NParks’ premises, the board has pasted decals to make windows visible at HortPark and Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve, Dr Tun added.

Dr Yong Ding Li, regional coordinator for migratory bird conservation at BirdLife, called the study “a pioneering contribution to conservation of migratory land birds in the context of Singapore’s urban sprawl, drawing heavily from the data contributed by hundreds of citizen scientists.”

The study concurs with Dr Yong’s own observations of migratory pittas being at high risk of colliding with lighted buildings and structures, he said.

He added: “More importantly, it provides, for the first time, strong evidence as to why this is happening.

“Going forward, we see that the conservation community needs to work more closely with building developers and NParks to ensure that building developments at landscapes of high sensitivity are mitigated and light pollution better managed, alongside initiatives and campaigns to reduce light pollution for migratory birds as what has been done elsewhere in the world.”

Those who find dead birds can contribute to research by contacting the Avian Evolution Lab at NUS on 8449-5023 via Telegram or WhatsApp.