SINGAPORE – In the wee hours of Jan 29, hurricane-force winds tore through northern Norway, ripping off some roofs, cutting electricity lines and halting flights. One of the areas affected was Tromso, known as the capital of the Arctic.

Two days later, central and northern Norway were slammed by the most powerful storm the country had seen in 30 years.

While strong storms are common during winter, those two were much stronger and their back-to-back occurrence is very rare, said Mr Petter Ekrem, a meteorologist for the Norwegian Meteorological Institute. Storm Ingunn on Jan 31 blew off a bus carrying 14 passengers and smashed the windows of a hotel in Bodo, a town just north of the Arctic Circle.

“This is what we can call the ‘Arctic winters version 3.0’, and we will see more of that coming,” said Dr Rolf Rodven, executive secretary of the Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme at the Arctic Council.

Speaking at the 2024 Arctic Frontiers conference on Jan 29 in Tromso, he was referring to how global warming is ailing the Arctic region almost four times as quickly as the rest of the planet.

“Since 1971, the Arctic has warmed by about 3 deg C, that’s just an average... And there is 9 per cent more precipitation now, most of it is taking place as rain, as we’ve just experienced today,” added Dr Rodven, as rain and gale lashed the Clarion Hotel The Edge, where the four-day conference was held.

The Arctic is profoundly changing, and Dr Rodven noted that there is limited baseline understanding of the region’s original state.

“On the other hand, you also need to grasp the dynamics of what’s going on now,” he added.

To that end, it is not just scientists living in the polar regions who are on a hunt to raise humanity’s knowledge of the icy high north. A handful of researchers from tropical Singapore are also venturing north to lend a hand.

Voyage on mystery sea

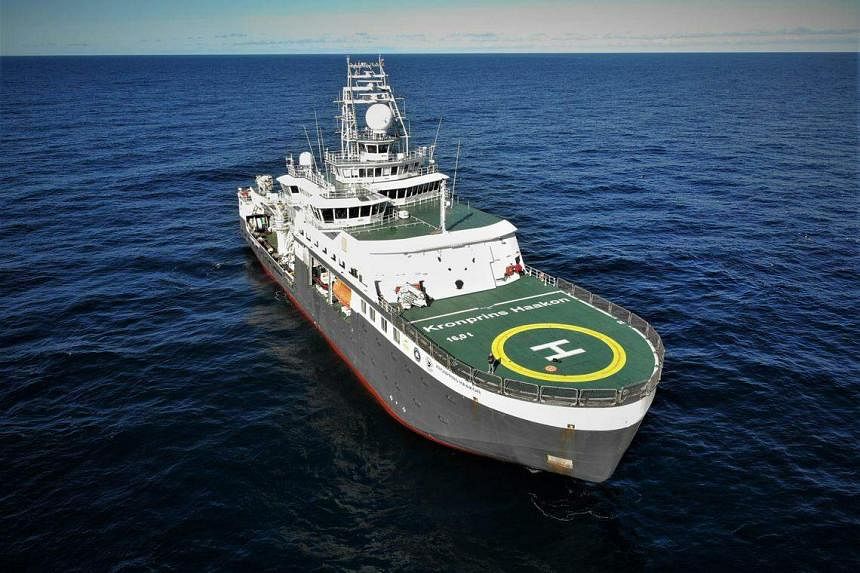

In April 2023, two researchers from Nanyang Technological University’s (NTU) Earth Observatory of Singapore joined an expedition to the Barents Sea, off the coasts of Norway and Russia. Dr Yan Yu Ting and Ms Toh Yun Fann were at sea on a research ship filled with labs for close to two weeks during the Arctic summer, when the sun does not set.

The aim of the exploration of the largely under-studied Barents Sea, led by the University of Tromso – The Arctic University of Norway (UiT), was to advance earth and marine science, and understand natural methane emissions – a potent greenhouse gas when it reaches the atmosphere – from the seabed.

UiT’s Professor Giuliana Panieri, the expedition leader, said: “The changes we are observing in the Arctic right now are very fast. And so the question is – are these fast changes affecting (overall) methane emissions? Methane stored in marine sediments could be triggered by warmer waters close to the sea floor.”

With the help of a remotely operated underwater vehicle, the Barents Sea adventure led to the discovery of a mud volcano, the second of its kind identified in Norwegian waters.

Dr Yan, a research fellow at the Earth Observatory of Singapore, was largely involved with slicing up and processing the sediments and mud samples collected by the vehicle.

“Cutting up sediment cores on the deck at about 2am, in 5 deg C temperature and in bright daylight is something I will never forget,” she said.

Ms Toh, a PhD student at the NTU Asian School of the Environment, was involved in processing data related to the underwater landscape and the water column with footage from the deep-sea vehicle.

Dr Yan, whose background is in geosciences, focuses on the reconstruction of past changes to the environment and climate by studying sediments. Ms Toh read marine and Antarctic science in university.

Their opportunity to venture into the Arctic came about when the Earth Observatory of Singapore’s director Benjamin Horton met Prof Panieri on a plane after he attended the 2022 Arctic Frontiers conference.

The expedition also provided sea-going training for young researchers to develop skills in working with Arctic marine samples and data.

Both researchers’ work in the Arctic Circle has not ended. In June, Ms Toh will join an expedition to the Norwegian-Greenland sea to study the seismic activities of a recently discovered hydrothermal vent.

Dr Yan will return to the Barents Sea with Prof Panieri and other academics in summer to zero in on the extreme marine environments of the Barents Sea where hot fluids and methane flow out.

On that voyage, Dr Yan will study foraminifera – tiny ocean creatures with shells smaller than a grain of sand. They are indicators of an area’s ecology, and will allow scientists to uncover how marine life there is faring amid the environment stressors, she said.

‘Hearing’ ice melt

Satellites are commonly used to track the melting of ice sheets. But scientists at the National University of Singapore (NUS) are relying on their sense of hearing to look for melting hot spots in the glaciers of Svalbard – a Norwegian archipelago between the country’s mainland and the North Pole.

Between June and August 2023, Dr Hari Vishnu and his colleagues did fieldwork at two glacial fjord regions in Svalbard. In one project, they deployed acoustic sensors near glaciers.

“When the glacier ice melts underwater, it produces a crackling that sounds like frying french fries, due to the explosion of air bubbles that were trapped in the ice. Our long-term goal is to develop this acoustic technique to monitor the ice loss at several glaciers over a long-term period,” said Dr Vishnu, a senior research fellow at the Acoustic Research Laboratory within the Tropical Marine Science Institute of NUS.

In turn, such studies will improve projections of how this ice loss translates into global sea-level rise, he added.

In another project, Dr Vishnu and his colleagues sent an NUS-built swimming robot to glacier cliffs where the ice meets the salty, warm ocean and melts. The yellow robot was equipped with sensors to record underwater sound, video, temperature and salinity changes.

To their knowledge, that was the first time such glacial data has been collected using robots.

“This is an interesting region with many physical unknowns... It is impossible for humans to study directly because the glacier is regularly calving,” he added.

Dr Vishnu and an NUS colleague just completed an 11-day quest at the South Pole on Feb 11, having expanded his research to the Antarctic.

Reconstructing sea-level rise

In August 2023, Dr Tan Fang Yi, a research assistant from the Earth Observatory of Singapore, and her team explored an Arctic saltmarsh in northern Norway to reconstruct sea-level changes in the area.

The tiny but mighty foraminifera, again, stored the clue to their research. Dr Tan and her colleagues collected sediment samples across the saltmarsh at increasing elevations above the sea.

Research fellow Yap Wenshu, who analysed the samples, said: “Scientists look for (foraminifera) shells under the microscope, like searching for tiny time capsules in the mud, to see what the ocean was like long ago.”

But it gets difficult when the shells are poorly preserved.

“That’s why we are exploring a new method called environmental DNA. It allows us to detect traces of their genetic material even when their shells are gone,” Dr Yap added.

Bridging Arctic-Singapore links

Since 2013, Singapore has been an observer state in The Arctic Council – the leading intergovernmental forum promoting cooperation among the eight Arctic states, which include Canada, Russia and the Scandinavian countries. The council has about a dozen observer countries that contribute to it primarily through working groups.

As several scientists and government officials said at the 2024 Arctic Frontiers conference, what happens in the Arctic does not stay in the Arctic. For example, melting ice sheets in Greenland will affect how much sea levels will rise in low-lying Singapore.

As Arctic Sea ice retreats, it could lead to the Northern Sea Route – a 5,600km shipping route – remaining open beyond the summer, which could have implications for Singapore’s status as a maritime hub. If more ships choose the Arctic route over the conventional Suez Canal-Malacca Strait route, fewer ships will pass through Singapore’s port.

But opportunities could also arise, as maritime firms here could be involved in infrastructural projects up north.

However, after Russia invaded Ukraine in early 2022, official meetings between member countries of the Arctic Council and its working groups stopped, said Ms Solveig Rossebo, a senior Arctic official at the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

This meant a pause or slowdown in some international collaborations. Singapore is part of some working groups within the council, such as the Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna – where the National Parks Board tracks Arctic migratory birds that refuel in Singapore during the winter.

Russia was chairing the Arctic Council until May 2023 when Norway took over.

Ms Rossebo said: “We are now working to hopefully start off virtual meetings for the working groups. (For) the migratory birds, for instance, we are now trying to get them going again. Singapore’s contribution in this is very welcome.”

Prof Panieri is also looking to work with NTU’s recently launched Climate Transformation Programme. “We are willing to support the training of students and also contribute our knowledge to the programme,” she said.

She added that she is keen on a project under the initiative to predict how climate change will affect human health. Singapore has been studying how climate impacts such as rising temperature and an increase in mosquito populations can affect health.

“There is not much done in the Arctic when it comes to the impact of climate change on health, and this is something I’d really like to develop together with Singapore colleagues,” she said.