SINGAPORE – In the nation’s most ambitious reef restoration to date, 100,000 corals will be progressively planted and grown in Singapore’s waters from 2024 to beef up the biodiversity of the waters and protect coastlines from waves and storms.

Over at least 10 years, baby corals, or coral fragments, will be reared in nurseries until they are large enough to be transplanted onto degraded reefs or new areas that can hold coral habitats.

About 60 per cent of Singapore’s reef area has been lost to land reclamation.

The remaining healthy reefs are mostly found in the southern islands, such as Pulau Satumu – where Raffles Lighthouse is located – Pulau Semakau, Pulau Hantu and the Sisters’ Islands.

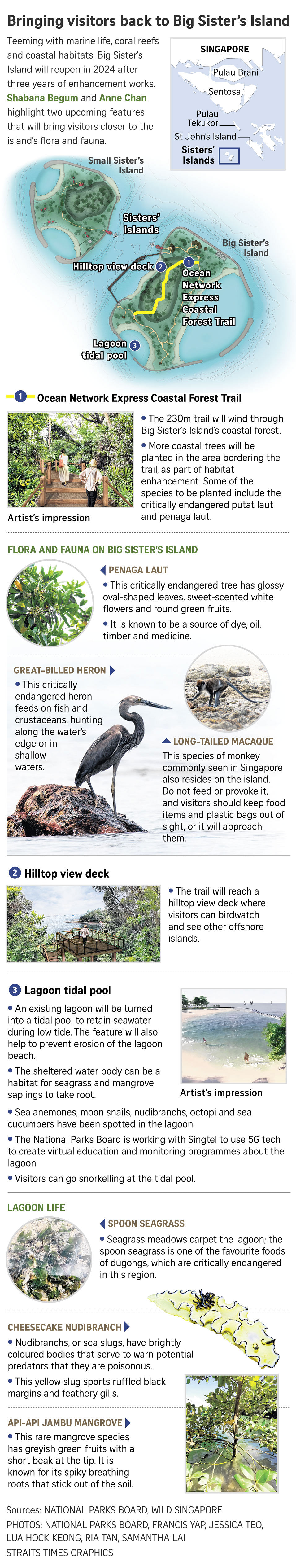

One of the Sisters’ Islands will also reopen for public visits in 2024.

Island hoppers can look forward to a more visitor-friendly Big Sister’s Island, which will have new features such as a forest trail that winds through the island, and a lagoon tidal pool that people can snorkel in.

The island, which is part of the 40ha Sisters’ Islands Marine Park, was closed from 2021 for enhancement works.

The 100,000 corals project, spearheaded by the National Parks Board (NParks), and updates on Big Sister’s Island were announced by National Development Minister Desmond Lee on Monday at the opening of the fifth Asia-Pacific Coral Reef Symposium at the National University of Singapore (NUS).

The 100,000 corals initiative will scale up the country’s existing coral restoration efforts, such as the Plant-A-Coral, Seed-A-Reef programme, which began in 2016.

The programme helped to expand the reefs of Sisters’ Islands Marine Park, with more than 700 corals planted and 16 artificial reef structures installed underwater, said Mr Lee.

The Republic’s waters are home to around 250 species of hard corals of various colours and shapes – about one-third of more than 800 species of the world’s hard corals.

“By introducing 100,000 corals, we hope that as they grow, they’ll increase in size and contribute to the overall increase in the spatial coral cover within the reefs in Singapore,” said Dr Karenne Tun, director of NParks’ National Biodiversity Centre.

Mr Lee said that work in the first few years will focus on growing capacity for coral cultivation, such as by expanding existing coral nurseries and exploring new methods to promote coral growth.

“This will provide us a strong foundation in subsequent years, when we significantly ramp up our efforts to transplant mature cultivated corals onto degraded reefs, and plant them in other areas,” he added.

While 100,000 coral babies will be planted, mature corals are tricky to count because the colonial creatures tend to grow and merge. Each species has different growth rates and they out-compete one another. As a rough gauge, four to eight coral fragments can be planted on an area of 1 sq m, giving the creatures enough space to grow.

Coral reefs here serve as a habitat for more than 100 species of reef fish, about 200 species of sea sponges, as well as rare and endangered seahorses and clams, among other marine life.

NParks is working alongside academic partners such as the St John’s Island National Marine Laboratory on this project, with the support of the Friends of Marine Park group.

The project comes at a time when warmer seas could be exacerbated by the looming El Nino climate phenomenon.

Elevated water temperatures and marine heatwaves can stress corals, triggering coral bleaching that reduces vibrant reefs to pale skeletons.

There is up to an 80 per cent chance of El Nino occurring in 2023, with signs suggesting that conditions could develop between July and September.

Past El Nino years of 1998, 2010 and 2015 saw mass coral bleaching affecting almost all corals here, said Emeritus Professor Chou Loke Ming from the NUS Department of Biological Sciences.

While most of the corals recovered eventually, about 10 per cent of them died after each El Nino cycle.

“What we observed is that corals appear to have developed some degree of adaptation so that they are less susceptible to the next sea-warming event.

“Transplants that we have put out in the field appear to have survived through these warming events,” added Prof Chou.

His colleague, Associate Professor Huang Danwei, will be studying ways to enhance the ecological resilience of coral reefs to climate change impacts, under the $25 million Marine Climate Change Science programme.

Prof Huang’s research is one of two projects announced by Mr Lee that received funding under the first grant call for the programme.

As for Big Sister’s Island, a new 230m trail will run through the island, allowing visitors to enjoy the coastal forest and birdwatch on a hilltop viewing deck.

It is called the Ocean Network Express Coastal Forest Trail, after the container shipping company that contributed $1 million to the building of the trail.

Another new attraction on the island will be a tidal pool developed from an existing wildlife-rich lagoon.

The pool will retain seawater during low tide, allowing mangrove saplings and seagrasses to take root.

Singtel, which donated $1 million to the development of the tidal pool, will also work with NParks to leverage its 5G technology and set up underwater cameras to help students and volunteers with biodiversity monitoring, said Mr Lee.

Since 2021, Big Sister’s Island has been undergoing works that include the repair of its seawalls and the upgrading of footpaths, toilets and shelters.

Small Sister’s Island is closed to the public, as it is used for marine conservation research.

The Sisters’ Islands Marine Park also includes the western reefs of St John’s Island and Pulau Tekukor which sits south of Sentosa.

Dr Tun added: “To ensure it is a sustainable marine park, we’ll be having solar farms, recirculating seawater to have fresh water on the island, and it should be, at the end of the day, a zero carbon footprint marine park.”

To get to Big Sister’s Island from 2024, visitors can either charter a boat or take a ferry from Marina South Pier. The frequency of ferry services and the number of people allowed on the island at any one time will be confirmed later, said Dr Tun.

Mr Stephen Beng, chairman of the Friends of Marine Park community, said: “I hope that the (marine park) will be another exciting destination for visitors to enjoy and appreciate the ocean environment... We want more to understand the many benefits marine protected areas provide, from safeguarding biodiversity and food sources to providing business and employment opportunities.”