SINGAPORE – From debut young-adult fiction author Kyla Zhao’s The Fraud Squad (Berkley Books) to Rachel Heng’s The Great Reclamation (Riverhead), which has a strong claim to be the latest great Singapore novel, 2023 has seen a bumper crop of local authors whose books have been picked up by international publishers.

In addition to novels by Zhao, 25, and Heng, 35, maid murder mystery Now You See Us (HarperCollins) by Singapore literature stalwart Balli Kaur Jaswal, 39, hit bookstores in March.

Meanwhile, Red Dust, White Snow (Fairlight Books), a Black Mirror-esque science-fiction work by new writer Pan Huiting, 25, is out on Aug 17.

Later in 2023, readers can look forward to Meihan Boey’s sequel to her successful The Formidable Miss Cassidy (2021), The Enigmatic Madam Ingram, which will be first released by Epigram Books and likely later by British independent publisher Pushkin Press.

Proving that the interest in the Republic’s stories has had ripple effects beyond the novel, a collection of personal essays by author and visual artist Tania De Rozario, 41, Dinner On Monster Island, is also set for February 2024.

It will explore, according to HarperCollins, “growing up as a queer, brown, fat girl in Singapore”.

Singapore ink’s going global has been a trend that has coagulated in the last few years, especially since Crazy Rich Asians (2013) by Singapore-born American author Kevin Kwan reached stratospheric heights with its 2018 Hollywood adaptation starring Constance Wu, Michelle Yeoh, Henry Golding and Gemma Chan.

That year alone saw at least two novels reach the international market: Rainbirds (2018), a small-town Japanese fever dream by Clarissa Goenawan, 35; and Ponti (2018) by Sharlene Teo, 36, whose tale of a misfit adolescent girl was praised by British author Ian McEwan even before the manuscript was finished.

Since then, a fresh crop of novels by recognised and fresh authors have found a ready audience among literary agents and British and American publishers.

It is a stark difference compared with the scene just one or two decades ago, when those in this rarefied club – including Catherine Lim, 81; Suchen Christine Lim, 75; Meira Chand, 81; and Shamini Flint, 53 – could still be counted with the fingers on one hand.

In this markedly different climate, it is possible to ask if Singapore’s novelists are just getting better and their craft now more sought after by readers far beyond the country’s shores – even if this international exposure also presents fresh challenges.

Daryl Qilin Yam, 32, author and managing editor of Sing Lit Station, the unofficial centre of Singapore literary activity, says the novel form is back in vogue.

He acknowledges the importance of Crazy Rich Asians in pushing Singapore into the Western consciousness, but says several important landmark titles in recent years have also been important in the revitalisation of the long form as a genre here.

He cites Ministry Of Moral Panic: Stories (2013) – written by Amanda Lee Koe, 35, and published by local publisher Epigram Books – which was the talk of the town when it was released.

Another Epigram Books title, The Art Of Charlie Chan Hock Chye (2015) by graphic novelist Sonny Liew, 48, also did its part in the transition from the “golden age of poetry” in Singapore in the early 2010s to the focus on fiction among writers today.

Yam, whose second novel Lovelier, Lonelier will soon be out with Singaporean-run, United States-based publisher Gaudy Boy, says: “I wouldn’t say it’s the golden age for Singapore fiction yet, but we are getting a taste of the idea.

“There is a sense of excitement surrounding this particular genre. Readers have always loved the long form, but the appetite for it has gone up over the years. The success of these other authors gives local writers confidence and persuades them to be more ambitious.”

Being published by these big, international publishers is a natural aspiration for writers, he adds.

“In terms of reach, advances and royalties, you can add another zero to what you’d get if you were published in Singapore. For as long as we’ve had bookstores, writers in Singapore have always wanted their books to be stocked alongside overseas titles, to be part of that marketplace of ideas.”

For Yam, the big surge came around 2018, with Jaswal’s funny Erotic Stories For Punjabi Widows (2017), Heng’s dystopian debut Suicide Club (2018) and How We Disappeared (2019) by Jing-Jing Lee, 38, a historical fiction piece about a young woman forced to work in a military brothel during the Japanese Occupation.

“These books don’t appear overnight. They usually take at least a year to get published. It means that even prior to this, some years before in the mid-2010s, there was already a sense that Singapore fiction could be a viable commercial enterprise.”

One of the pioneers of being published overseas is Suchen Christine Lim, author of novels like Fistful Of Colours (1993), A Bit Of Earth (2001) and The River’s Song (2014).

She says the lack of Singapore titles going international 10 years ago was natural, because those of her generation did not have knowledge of how to go about being published overseas.

Though her commissioned non-fiction collection Hua Song: Stories Of The Chinese Diaspora was published by Longriver Press in the US in 2005, her own fiction would have to wait till 2014 to be picked up, after an entrepreneurial agent from literary agency Jacaranda reached out.

Lim says there has been a drastic change in how the news of a novelist being published overseas is received.

“In the early days, there was still a bit of hoo-ha, but now, it’s quite usual. The literary agencies and Western publishers have already established branches here.”

For her, the biggest difference in being published overseas has been in opportunities and reputation, even if “I don’t go after these things”.

When The River’s Song was published, she received invitations to read at writing and book festivals in Melbourne and New York.

“By now, overseas readers and publishers are sophisticated enough to accept the Englishes from other countries,” she adds. “Even my novels that were published in Singapore, like Dearest Intimate (2022), which had a cross-dressing opera actress, was understood by overseas readers who have had positive reactions to it.”

Local publishers’ existential dilemma

Despite being credited as integral to the renewed success of the novel, Epigram Books founder Edmund Wee is worried.

More good authors going to international publishers means Epigram Books might become effectively a second choice.

After nurturing and spending long hours editing rookie novelists’ manuscripts, these authors going on to ink deals with other publishers represents an erosion of Epigram Books’ future income.

In the last year alone, Mr Wee says, three of Epigram Books’ writers signed with publishers in the US and Britain for their works to be distributed overseas: Karina Bahrin, 53, for The Accidental Malay (2022) with British publisher Picador, an imprint at Pan Macmillan; Boey for her Miss Cassidy series with Pushkin Press; and Jeremy Tiang, 46, with State Of Emergency (2017) with New York’s World Editions.

These publishers usually agree to acquire these books only if they are given world rights, after which they can resell these rights for higher amounts to other publishers and produce competing editions with Epigram Books.

If these do well, the publishers reach out to these authors directly, cutting out Epigram Books as the middleman.

Mr Wee says: “This is, of course, good for the author and even for us initially. But after that, the author will go with the bigger publisher because it can offer a bigger advance and can promote the author more.

“The Government is always telling us to go to Frankfurt to sell the books, sell the rights. What it doesn’t understand is we are killing ourselves when we lose these authors who are on the verge of becoming recognised.”

He says this is an existential dilemma for all small publishers, citing an example of a big publisher offering not 10 times, but 100 times the advance that another smaller one could afford.

“There’s no way we can compete and we certainly can’t in good conscience tell the author to stick with the original publisher. The only way is to get bigger, but our market is small and the gap is impossible,” he adds.

Aware that competition for book rights will only get fiercer with Western readers clamouring for non-white stories, Mr Wee has raised the issue with the National Arts Council, but does not have a solution himself.

He says some form of protection is needed and suggests compensation each time the rights to a book is sold. But this, too, is small recompense and unsustainable in the longer term.

On the importance of local publishers like Epigram Books, he adds: “To get publishers interested, you need a literary agent. You can write to them, but it’s much easier when you already have a book published by us and you can show it to them.

“You need people like us in the ecosystem – it’s an existential dilemma, not just local publishers trying to get money.”

Retaining the Singapore flavour

The rise of the internationally published local author has also created a different set of questions for writers.

In the process of editing, it is not unusual for publishers to request authors to make changes so certain words are more comprehensible to Western readers.

Heng, whose The Great Reclamation follows a kampung boy growing up in the tumult of 20th-century Singapore, wrote in Time magazine in June that a German reader e-mailed her asking why she had neglected to include a glossary for the Singlish words she sprinkles throughout.

That comment “betrays the entitlement of someone accustomed to a world in which they are always the implied audience”, says Heng, who makes an impassioned defence of why she does not translate non-English words in writing.

Like Indian author Salman Rushdie’s quest “to write in an English that wasn’t owned by the English”, she says, naturalising the diversity of English is so that her Singaporean characters are not positioned as something foreign to be made legible for the white Western reader, and so she does not exclude Singaporean readers.

Other authors also say they are unlikely to accept changes to their language or story if they feel those choices are made to reduce the Singaporean-ness of their writing.

For the most part, British and US publishers have become more open to foreign words and stories, and are respectful of the world the characters live in.

Jaswal, who uses Singlish and Tagalog in Now You See Us, says “long gone are the days where writers had to include footnotes to explain italicised ‘foreign’ words’”.

Her novel was promoted as Crazy Rich Asians meets The Help, a 2009 bestseller by Kathryn Stockett about African Americans working in white households – not totally accurate, but a concession she was willing to make for marketing.

The writing itself, though, retains its integrity.

“During the editing process, there have been a few places where I had to do some brief contextualising, but this is what I have to do no matter what I write,” she says.

“My novels are about people from minority groups living in places where their narratives, languages and customs are unfamiliar to the larger majority.”

The Fraud Squad’s author Zhao says she changed her literary agent after she was asked if she would consider setting her high-society imposter tale in New York.

It was something she refused to compromise on, as the Singaporean food and places were important to her as a way of connecting with home while she was living alone in California during the pandemic.

Sing Lit Station’s Yam says Singaporean readers should take pride in the success of these authors and let them write the stories they want, whether these are set locally or overseas – such as Goenawan’s Rainbirds, The Perfect World Of Miwako Sumida (2020) and Watersong (2022), which are all set in Japan.

“They should always be free to write whatever they want and, as readers, it’s our job to honour whatever they want to write,” he says.

Whether local authors would start writing stories that cater to a global market is also “not a very productive question”, he says.

“I do think it’s an inevitability that when stories enter a non-local marketplace, the stories writers tell end up not necessarily local – but that has nothing to do with whether it’s good or enjoyable, and whether you are touched.”

Five local books published overseas in 2023

1. The Great Reclamation by Rachel Heng

Fiction/Riverhead/Paperback/451 pages/$28.03/Amazon SG (amzn.to/43TkxdC)

Rachel Heng’s follow-up to her 2018 debut Suicide Club sees a kampung boy discovering disappearing islands before they are caught up in Singapore’s rapid modernisation.

It takes a sweeping look at the city-state’s history from the 1940s to 1960s, covering the tumultuous days of the Japanese Occupation, the Chinese middle-school student riots and the rise of the “Gah Men”.

The Great Reclamation is a historical epic and coming-of-age story rolled into one, with elements of the fantastical sprinkled in.

Key to developments is land reclamation, the audacious act of which has increased Singapore’s land mass by some 25 per cent since the 1960s.

The Straits Times’ book reviewer Olivia Ho called it “a powerful reclamation of its own, reconstructing in fiction that which has long vanished in reality”.

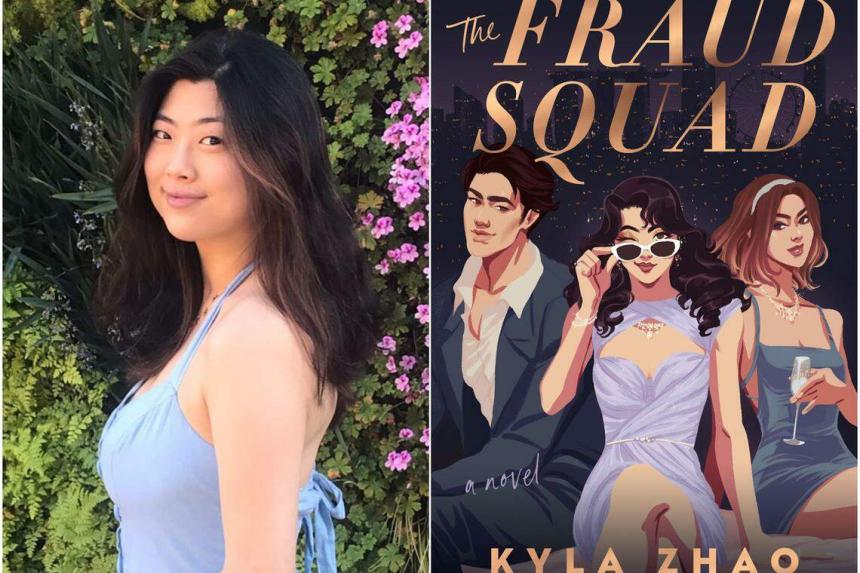

2. The Fraud Squad by Kyla Zhao

Fiction/Berkley Books/Paperback/368 pages/$21.06/Amazon SG (amzn.to/3DQnAbG)

Kyla Zhao was an editorial intern at Vogue Singapore when she scored a two-book deal for a six-figure sum each.

In The Fraud Squad, young Singaporean Samantha Song is stuck in a junior public relations job and far from landing the job of her dreams of writing for a high-society magazine, until her scheming opens the doors to the socialite world.

The novel, which resembles young-adult fiction, expertly weaves between commentary about the lives of the Singaporean middle class and name-dropping expensive designers at the best parties.

It packs a punch, encouraging readers to re-examine well-intended policies that have made it difficult for one to enter the workforce without a university degree, while being unafraid to poke fun at some of the ridiculousness that comes with money.

3. Now You See Us by Balli Kaur Jaswal

Fiction/HarperCollins/Paperback/325 pages/$30.24/Amazon SG (amzn.to/3DKaRaz)

When a Filipina domestic worker is arrested for her employer’s murder, all of Singapore seems to think she is guilty – except for a trio of unlikely sleuths, who set out to find the real culprit and exonerate their countrywoman.

Now You See Us is Balli Kaur Jaswal’s fifth novel, a smart, funny read that astutely blends social satire with intricately plotted mystery.

For the novel, Jaswal interviewed a number of domestic workers, which enables her to pack scenes with vivid detail.

As a whodunnit, there are twists aplenty and a satisfying ending, opening readers’ eyes to the invisible world that exists alongside theirs.

4. Red Dust, White Snow by Pan Huiting

Fiction/Fairlight Books/Paperback/192 pages/$24.63/Amazon SG (amzn.to/3YrA43l)

Set for release on Aug 17, Pan Huiting’s fantastical debut novel kicks off with an office worker receiving a mysterious device promising to transport her to a parallel universe.

That night, she visits the place in her dreams, only to return to the same dream the following night – and soon finds herself reluctant to wake up.

A wry satire of the way the virtual has bled into people’s lives, it has already been praised by early readers for its sprawling imagination and luminous writing.

One of them, Sing Lit Station’s Yam, describes it as a “dizzying, inventive, page-turning debut”. Pre-orders are open.

5. The Enigmatic Madam Ingram by Meihan Boey

Fiction/Epigram Books and Pushkin Press/Paperback

This second instalment of Meihan Boey’s popular Miss Cassidy series follows Letty Ingram, a half-Malayan woman raised in Britain, who has suffered under a strange curse her whole life.

She returns to Singapore to seek the help of Madam Kay, a Chinese medium – but Madam Kay’s whole family gets involved, including her sister, her father and their unusual mutual friend, the formidable Miss Leda Cassidy.

The first novel, 2021’s The Formidable Miss Cassidy, was told from the perspective of this character, who arrives in Singapore from Scotland to serve as a paid companion to delicate Sarah Jane, the last surviving child of the beleaguered Bendemeer family.

She establishes that the Bendemeers have been killed not by tropical fever, but the pontianak haunting their garden, and sets about devising a solution.

The charming adventure was an utter delight, and the second book promises to take things up a notch.