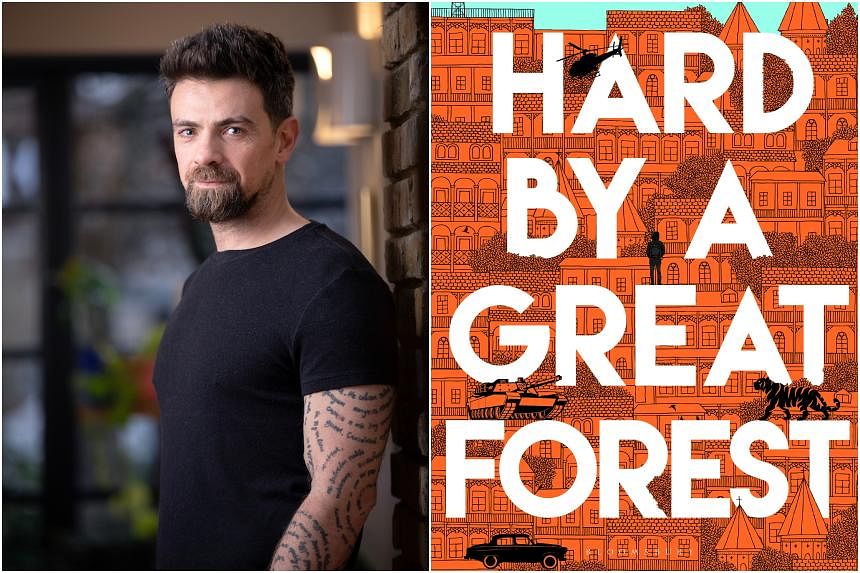

SINGAPORE – It is difficult to read Georgian author Leo Vardiashvili’s Hard By A Great Forest without being sucked into a game of trying to separate truth from fiction.

Drawing from the author’s own move from Georgia to London when he was 12, his debut follows protagonist Saba as he makes a belated return to his home town of Tbilisi, after the mysterious disappearance of his father and brother.

The tenor of this unplanned homecoming is one that hovers between the barely believable and the fantastical, involving cryptic Hansel and Gretel references, ghostly voices and vengeful officials.

A surreal clash of severe dysfunction with modernity is immediately established. Upon Saba’s arrival, his taxi encounters Boris the hippopotamus in the process of wrecking a Swatch shop. A flood has set the erstwhile residents of the Tbilisi zoo loose, a real-life event that happened in 2015.

Vardiashvili says: “The incident with the zoo just fell into my lap. I saw news reports and it was too good to pass up. There were videos of wolves in the supermarket, an escaped tiger. When I was a kid, they definitely had names. I don’t know if they still do.”

Vardiashvili, 41, is a tax adviser by day, but has wanted to be an author since he read J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord Of The Rings as a child.

His family moved to London after the Georgian Civil War from 1991 to 1993 when it became obvious that things were not going to improve.

But in the book, he has shifted this timeline so their escape is more chaotic, an abrupt choice made on the first page after a stray tank shell “breaks the sound barrier by your bedroom window and deletes the corner grocery shop”.

While Vardiashvili’s mother in reality managed to join up with the family in London quite quickly, Saba’s family had to desert their mother. The book begins: “Where’s Eka? We must have asked a thousand times.”

Vardiashvili makes reassurances that his and Saba’s lives diverge once Saba gets to Tbilisi, though he has retained some real-life anecdotes. One of these involve a rooftop party amid a shortage of food and water and regular cuts in electricity during the civil war.

“I really liked that they made that choice. It was between that and being miserable.”

Otherwise, he was too young to understand the war’s devastation when he was living through it. He and his friends collected bullet casings on the way to school and compared them.

“It seemed like a game sometimes, like fireworks. It’s weird to have it as a fun memory. Obviously, now I realise that there were people getting hurt.”

On his own return to Georgia that inspired the book and led to several more return trips for research, he adds: “Seeing my family again after 17 years was very strange. Seeing the city itself was weirder. In the time we were away, it went from former Soviet colony to having skyscrapers. There were adverts in the streets. It’s a mixture of ancient architecture and very modern stuff.”

Saba’s search leads him to mountainous villages and contested borderlands, where he is shot at. Historically, Georgians have escaped to seek refuge in these uninhabitable areas whenever they faced invasion, whether from Ottoman or Russian forces.

For research, Vardiashvili hiked in a series of villages near Ushguli. In England – a relatively flat country – he still misses the Georgian mountains, where he skied as a child.

“There’re lots of watchtowers and, historically, all kinds of cultural treasures would end up there during wartime – texts, frescoes, paintings. It was a case of me just taking notes while being on holiday.”

An English literature student at the Queen Mary University of London, he is keenly aware that not many Georgian stories have made it to the Anglophone mainstream. He is much more familiar with English than Georgian literature, but cites Georgian-German author Nino Haratischwili as an influence.

Haratischvili’s The Eighth Life (For Brilka) (2014) is an almost 1,000-page epic of a Georgian family during the 20th century and has won several literary awards in Germany, where the author has lived since 2003.

“There isn’t much Georgian stuff. It doesn’t get out there easily,” Vardiashvili says. “It’s a tiny country with only three million people and the language is very different. It’s not a Latin-based language, so it’s also very hard to translate.”

Hard By A Great Forest is the first story he has written about Georgia. Before that, he tried his hand at short stories, including one about a person visiting his dying friend in hospital and trying to help him along.

Asked if he feels a responsibility to keep writing about Georgia, he replies quickly: “No, I definitely don’t want to be that guy. I’m ready to move on.”

- Hard By A Great Forest ($27.40) is available at Amazon SG (amzn.to/3vdgOMG).