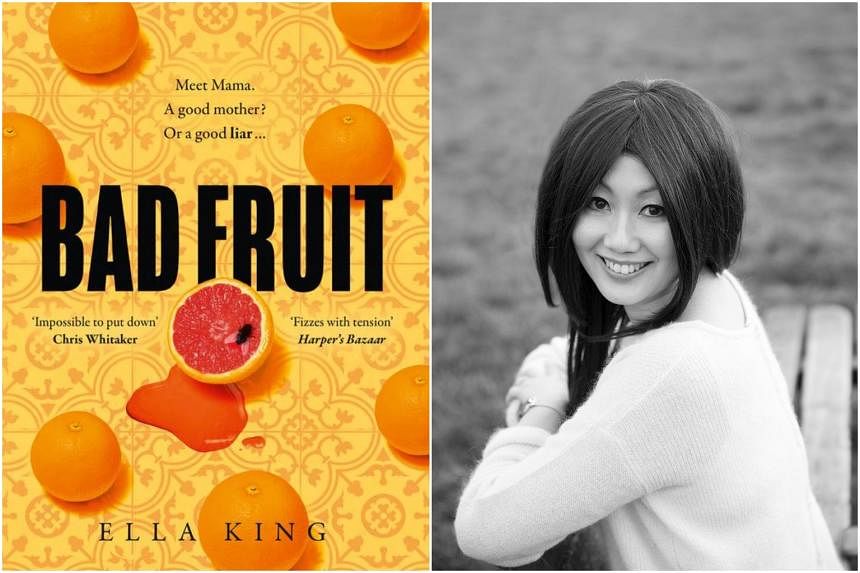

BAD FRUIT

By Ella King

Fiction/HarperCollins/Paperback/312 pages/$25.24/Buy here

3 out of 5

Lily's mother will drink only expired juice. To make sure it is to her taste, she has Lily test it first. Every night, Lily swills rancid juice, gags and spits it down the sink plughole. Blood orange juice, three days off. Perfect.

There are plenty of toxic mother-daughter relationships in fiction, but Britain-based Singaporean Ella King's debut Bad Fruit squeezes out something especially rotten.

Lily, 18, should be excited about starting at Oxford University. Instead, she is spending a sweltering London summer trying to keep the peace in her train wreck of a family.

Her volatile mother May believes Lily's father Charlie is having an affair with their son Jacob's ex-wife. Lily and Jacob's older sister Julia, a provocateur by instinct, makes things worse by needling May to greater heights of rage.

On top of this, Lily is beginning to have flashbacks to a life that is not hers. She determines they belong to May, who left behind a mysteriously tragic past in Singapore to marry a white Englishman.

But May's past - the emerald Peranakan shophouse in Joo Chiat she claims to have grown up in, the Oxford scholarship she supposedly had to give up when her parents died in a car accident - turns out to be full of holes.

As the flashbacks grow more intense, Lily frets that she will soon be unable to tell where she ends and the mother who has overshadowed her whole life begins.

King has produced a fascinatingly horrible psychological thriller. There is an addictive quality to the story, if only because you want to see exactly how deep the rot goes.

May, in particular, is a mother out of nightmares, tyrannical and manipulative one moment, child-like and vulnerable the next.

Lily maintains her position as favourite offspring via a disturbing "yellowface" ritual, in which she puts on make-up and contacts that make her look more Chinese and dyes her hair black to resemble her mother. Underneath it all, however, Lily remains May's "whitest child".

Peranakan dishes are associated with family trauma. Lily, making kueh kapit to welcome her mother home, imagines the iron biscuit press as a weapon to sear a pattern on a cheek.

The novel delves into the dark consequences of inherited trauma and generational abuse.

It is unfortunate that it also relies on an exoticised vision of Singapore, refracted through May's twisted memories and Lily's tourist perspective.

Lily, reflecting on London's heatwave, remarks that the weather would never make the news in Singapore. This reviewer, who has written her fair share of weather stories for the national daily, begs to differ.

Biracial Lily is told she has “ang moh gui eyes, white devil eyes, eyes that in Singapore, I would have been drowned for” – a sensational line that feels plucked from some melodramatic colonial-era romance, and does not befit a piece of contemporary fiction.

Such inconsistencies may be of little note to an international readership, but for Singaporeans, it may leave a sour taste in the mouth.

If you like this, read: Burnt Sugar by Avni Doshi (Hamish Hamilton, 2020, $19.80, buy here, borrow here), about a toxic mother-daughter relationship in Pune, India. Artist Antara resents having to care for her dementia-stricken mother Tara, who years ago fled her unhappy marriage for an ashram.