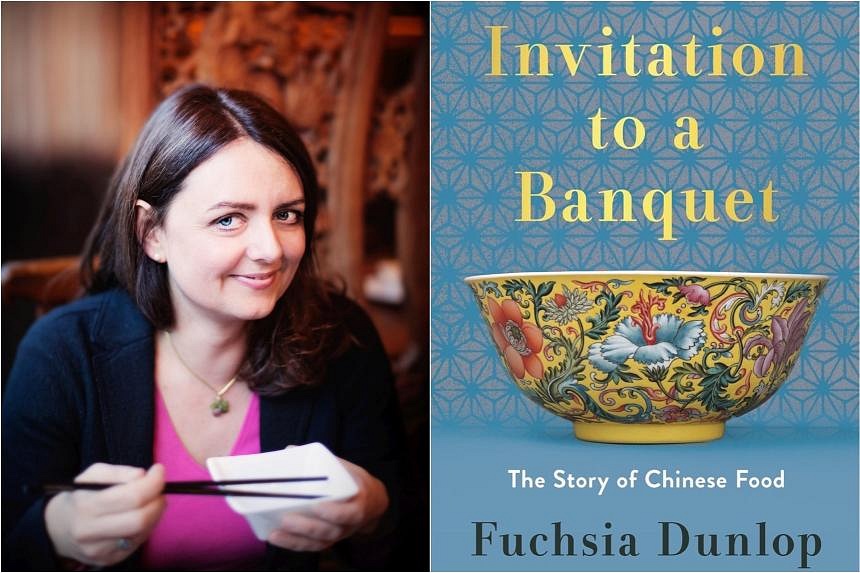

Invitation To A Banquet

By Fuchsia Dunlop

Food history/W.W. Norton & Company/Hardcover/466 pages/$50.16 from Amazon SG (amzn.to/3tT8UXZ)

5 stars

This is the most fun and informative book about Chinese food I have ever read.

I should add the caveat that, having struggled with the Chinese language all my life, culinary texts in the original Chinese language are way beyond my ken.

So, ironically, it is British food writer Fuchsia Dunlop who has unlocked Chinese culinary secrets for this reader in the past with her practical cookbooks about the wonders of Sichuan and Jiangnan cuisines.

Fans of Dunlop’s writing will know what to expect: Conversational anecdotes about the Sinophile’s decades-long engagement with China, deep and scholarly detours into the geographical and political histories of Chinese cuisine, and lucid breakdowns of sophisticated cooking techniques.

In fact, long-time readers who have followed her writings over the years will recognise key stories about her life and encounters. Yet, this is a comforting familiarity, rather like shooting the breeze with an old friend recalling milestone moments with affection and nostalgia.

For newcomers to Dunlop’s writing, it is an exhilarating, engaging and oftentimes laugh-out-loud funny love letter to Chinese food.

Dunlop structures the chapters loosely according to four themes – Hearth, Farm, Kitchen and Table.

Hearth begins literally at the beginning, with the Chinese version of Prometheus – the mythic leader Suiren who taught man to make fire.

Then comes the revelation that rice was not one of the original sacred grains of Chinese food. Rather, it was millet which ruled ancient China, with nearly a hundred varietals cultivated in northern China by the sixth century AD.

Paired with millet is geng, a stew packed with cut ingredients and thickened with starch. Dunlop calls geng “the original cai, the ur-dish of Chinese cuisine”, the first dish served at Han Dynasty banquets some 2,000 years ago.

She builds on this sturdy foundation an edifice of many rooms that reflects the diversity of Chinese food.

Farm encompasses multiple topics ranging from the co-evolution of agriculture and cooking to the creativity of the Chinese cook: “The question, for a Chinese chef, is not ‘is this edible?’ but ‘how can I make this edible?’”

This latter insight is typical of Dunlop, for whom food is not just a purely sensory delight and epicurean pleasure, but also a gateway to understanding a people and culture. Hence, her narrative ranges far and wide.

She quotes from literary writings such as poets who write swooningly about Chinese food, as well as citing archaeological sources that reveal the roots of produce and origins of dishes. She unpicks centuries-old Chinese philosophical ideas that link ethics with eating and politics with consumption.

She also addresses, calmly and with nuance, how racism and cultural difference have powered Western narratives about Chinese food.

The Western stereotype that Chinese food is salty, oily and unhealthy is, she points out, based on cheap Chinese restaurants in the West which evolved to cater to Western palates and bear little resemblance to actual Chinese food.

She addresses in a chapter, The Lure Of The Exotic: “An infatuation with arcane foodstuffs runs deep in Chinese history.”

She sets this love in the context of “a culture in which eating adventurously was understood as a joyful way of inhabiting and experiencing the world”.

But she also acknowledges that in a modern world where extinction is a major concern, the appetite for exotic animals is “grotesque”. She points out that such behaviour is also controversial in China, adding: “In modern China, lavish and exotic eating is associated with political corruption and the greed of government officials.”

While the book addresses many such heavyweight topics, there is also lightness and joy in Dunlop’s writing. She describes geng as “a swirling kaleidoscope of colour, like Venetian glass made edible”.

She borrows her father’s coinage of foods with “high grapple factor” to describe uniquely Chinese delicacies, such as chicken feet: “Eating it is a negotiation; you cannot simply chomp and swallow.”

Even for someone who has grown up with Chinese food, there are revelations to be gleaned from Dunlop’s astute observations.

Chinese restaurant menus are “notoriously long” because “a limited set of ingredients, cut into small pieces of various possible forms, can be spun together into almost infinite combinations, like lottery numbers”.

I now have a new appreciation of stir-frying after her explanation of the challenges of cooking dishes over high heat in a volcanic restaurant kitchen: “A second’s inattention can make the difference between ravishment and ruin… a stir-fry, like a calligraphic work, must be executed perfectly the first time: once the food is in the wok or the ink is on the paper there is no going back, no second chance.”

This book does not just capture the gloried past of Chinese cuisine, but it also addresses the future of food.

She laments the “hotpotization” of Chinese restaurants and the difficulties of cultivating a new generation of chefs – a complaint eerily familiar to Singaporeans worried about the future of hawker food.

But she also cites exciting examples of young restaurateurs who are finding new spins to traditional techniques and points out that Chinese culinary traditions centred on freshness and vegetable-forward dishes can offer lessons to a modern world seeking more sustainable modes of nutrition.

This is a book that lives up to its title – an invitation to consider one of the great gastronomic traditions of the world and a most dizzyingly fabulous banquet indeed.

If you like this, read: The Food Of Sichuan by Fuchsia Dunlop (Bloomsbury, 2019, $59.37, Amazon SG, go to amzn.to/3ScRPld). This is a thoughtfully revised edition of her landmark 2003 cookbook, Land Of Plenty: A Treasury Of Sichuan Cooking, which adds more than 70 new recipes. Its nuanced understanding of Sichuan spices and seasonings is an essential curative to the mala craze.