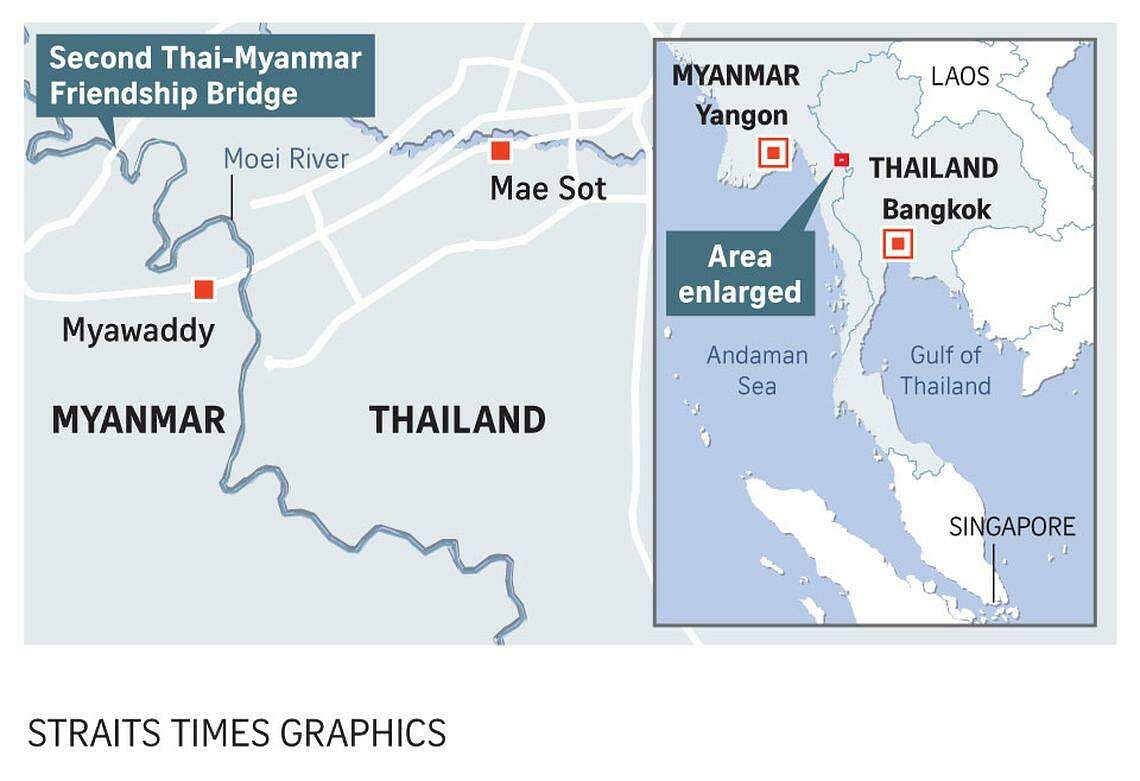

MAE SOT, Thailand – Hundreds of Myanmar civilians fled to western Thailand on April 20 after clashes broke out between Myanmar military and resistance forces near a bridge linking the two countries.

The Second Thai-Myanmar Friendship Bridge links the strategic border township of Myawaddy and Thailand’s Mae Sot district.

The fighting erupted more than a week after ethnic armed group Karen National Union (KNU) and its allies overran Myanmar military bases around Myawaddy – a key trading hub through which over US$1 billion (S$1.36 billion) of trade passed in the fiscal year ending March.

The military has been grappling with growing armed resistance since seizing power from the civilian government in a 2021 coup. Since October 2023, it has lost control of key territories near the China-Myanmar border to ethnic armed groups.

According to the KNU, troops from the Myanmar military’s Infantry Battalion 275 – whose base had been raided by the KNU and allied groups – had sought refuge in an area near the Myanmar side of the bridge.

This bridge is one of the two linking Mae Sot and Myawaddy through which Thailand had sent its first tranche of aid in March, as part of a plan to create a humanitarian corridor to Myanmar.

Thai Prime Minister Srettha Thavisin posted on X, formerly Twitter, on April 20 that he was “closely monitoring” the situation with concern.

“I do not desire to see any such clashes have any impact on the territorial integrity of Thailand, and we are ready to protect our borders and the safety of our people,” he wrote. “At the same time, we are also ready to provide humanitarian assistance if necessary.”

Thai media outlet Matichon reported that more than 1,200 people fled to Thailand on the morning of April 20 amid bombardment by military aircraft.

Earlier, the KNU said it had blocked the advance of the junta’s reinforcements at the foot of the Dawna mountains in eastern Myanmar.

Even then, locals were on alert for air strikes by the military.

Some Myawaddy residents told The Straits Times that they had sent their relatives over to Mae Sot for safety while they remained on alert in their half-empty Myanmar homes.

Beyond the battles against the junta, locals said they are unsure about the ensuing balance of power in Myawaddy.

Various ethnic Karen armed groups operate in the Myawaddy area. Myawaddy residents said the most visible troops within the town have so far been from the Karen National Army (KNA), a group which had up till January belonged to the junta-aligned Kayin state Border Guard Force.

Accused of shielding and profiting from international cyberscam operations in the nearby district of Shwe Kokko, the group had reportedly pushed back on the junta’s attempt to rein in these activities and declared its independence, renaming itself the KNA.

It is not clear what negotiations are taking place between the KNU and KNA, but speaking to ST on April 19, KNU spokesman Saw Taw Nee described the situation as “a little bit messy”.

Asked if the KNA was running Myawaddy town, he replied: “We cannot clearly say that. We are planning to introduce a KNU administration, but we cannot do that now, as we have to stop the State Administration Council from moving into Myawaddy town.”

The State Administration Council is the name the junta has given itself.

The KNU had earlier issued a statement where it, among other things, promised to “prevent illicit businesses, contraband trades and human trafficking” in Myawaddy, raising questions over whether it would trigger conflict with the KNA.

Some Myawaddy residents had already relocated across the border as a precaution before the April 20 clashes.

Ms Naw Nyimalay, who declined to reveal her real name for security reasons, packed the most expensive items in her clothes shop in Myawaddy and sent them to a friend in Mae Sot for safe keeping.

On April 8, the single mother, who is in her 40s, crossed the bridge to Thailand, hoping to settle in Mae Sot with her mother and two children, who had arrived separately.

Ms Naw Nyimalay took with her 200,000 baht (S$7,400) in savings, but left behind in Myanmar a house, shop and car – all of which she thinks will find few takers given these uncertain circumstances.

Struggling to find a suitable home in Mae Sot, she leased an old wooden house for 5,000 baht a month. It turned out to be haunted, she claimed. When ST visited her, her family had laid out their bedding in the patio.

“We can’t sleep peacefully in the bedrooms, so we are now looking for a new place,” she lamented, but added that there are not many houses to choose from because many Myawaddy residents are also looking for safe havens.

Still, she said: “I choose to stay here and struggle.”

Facing equal uncertainty is Mr Than Gae, whose family of six relocated to Mae Sot one month ago amid fears of air strikes near their village in Myawaddy township.

“We carried some clothes with us, and that was about it. And we buried our pots and pans under our house so that we can use them when we return,” he said.

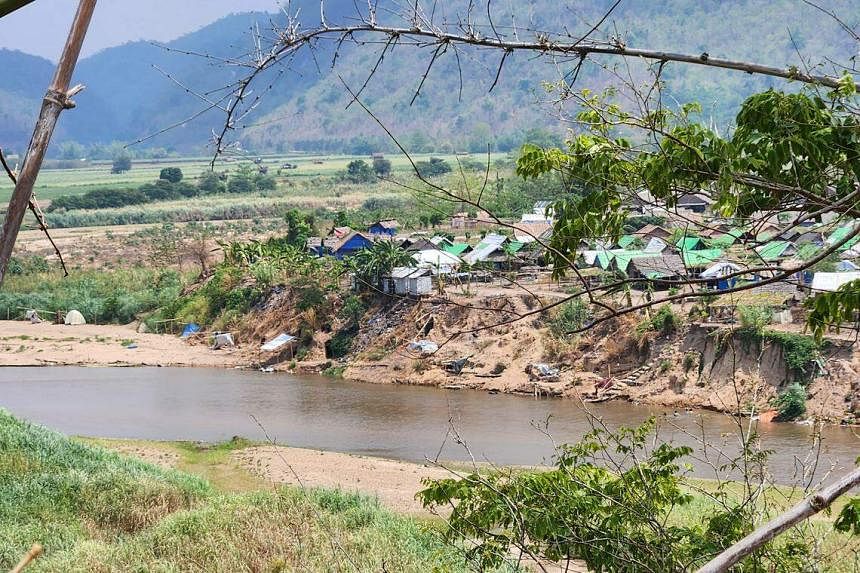

Their house in Mae Sot is little more than a shack on stilts surrounded by walls of corrugated metal, rented for 1,000 baht a month. Showers are taken in the open, from a barrel of water.

As Mr Than Gae, 36, did not use an official border crossing to enter Thailand, he lies low to avoid arrest by the Thai police when he is not working as a labourer on a Thai construction site.

“Usually, during Thingyan (the Myanmar New Year festival), we would play with water in our village, drink and chat with friends and make donations to temples,” he said.

This year, his family shared a meal and watched updates about the situation in Myanmar on their mobile phones.

While the rest of his family are eager to return home when conditions are safe, Mr Than Gae plans to stay away to avoid being drafted under the conscription programme imposed by the junta in February.

“I worry about that as I don’t want to be a soldier.”

- Additional reporting by Naw Betty Han